Federal Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos said Monday that the government will invest $17.9 million to increase access to HIV testing in remote communities and among hard-to-reach populations.

But advocates who work on issues related to HIV say the announcement, made at AIDS 2022, the 24th International AIDS Conference in Montreal, needs to be followed by more action.

Duclos said the government will use $8 million to fund the distribution of self-testing kits, which can be acquired anonymously and used at home, while the other $9.9 million will go toward expanding HIV testing in northern, remote or isolated communities.

"We know that HIV is preventable, yet the rates of HIV infections remain high in Canada and in other countries. Providing individuals with access to testing, treatment and care can help reverse this trend. Removing barriers is the key to ending the AIDS pandemic," Duclos told reporters.

He said access to testing – and the treatment it enables – is more difficult in some communities, including Indigenous and racialized communities.

Jody Jollimore, executive director of the Community-Based Research Centre, a Vancouver-based organization that advocates for the health of people of diverse sexualities, said the announcement is a good first step.

"Obviously, this was not what we were hoping for," Jollimore told reporters at the same news conference.

His organization is part of a coalition of community groups that has been calling on Ottawa to increase funding for addressing HIV from around $73 million a year, to $100 million a year.

Jollimore said that while helping ensure people know their HIV status is one of the most important actions the government can take – in part because treatment can prevent people from passing the disease to their partners – more action is needed.

"On its own, it is not enough. Communities affected by HIV continue to face stigma and discrimination that put us at an elevated risk of HIV infection and acts as a barrier to testing treatment and care," he said, adding that access to prevention tools, like pre-exposure prophylaxis, is inconsistent across Canada.

He said an estimated 17,000 people in Canada have HIV but don't know their status.

Ken Monteith, executive director of a network of AIDS organizations in Quebec called COCQ-SIDA, said the federal government also needs to address the criminalization of non-disclosure of HIV status and sex work as well as the war on drugs, which can make prevention more difficult.

"Criminalization, at all levels, prevents us from protecting the health of our communities," he told reporters.

Last week, Justice Minister David Lametti said the government will study changing the law that allows people to be prosecuted for aggravated sexual assault if they do not disclose their HIV status, even if treatment has rendered them unable to transmit the virus.

Ottawa estimates that 63,000 people are living with HIV in Canada.

Earlier Monday, the director-general of the World Health Organization told the conference that growing inequality could reverse a decade of progress made in the fight against HIV.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who addressed the AIDS 2022 conference by video, said the "overlapping crises" of COVID-19, inflation and cuts to foreign aid by wealthy countries are accelerating inequality and disrupting health services.

While the number of HIV infections and deaths related to AIDS are much lower than they were a decade ago, progress could be easily reversed, he added.

Globally, approximately 1.5 million people were infected with HIV last year and an estimated 650,000 deaths were linked to AIDS, according to the United Nations.

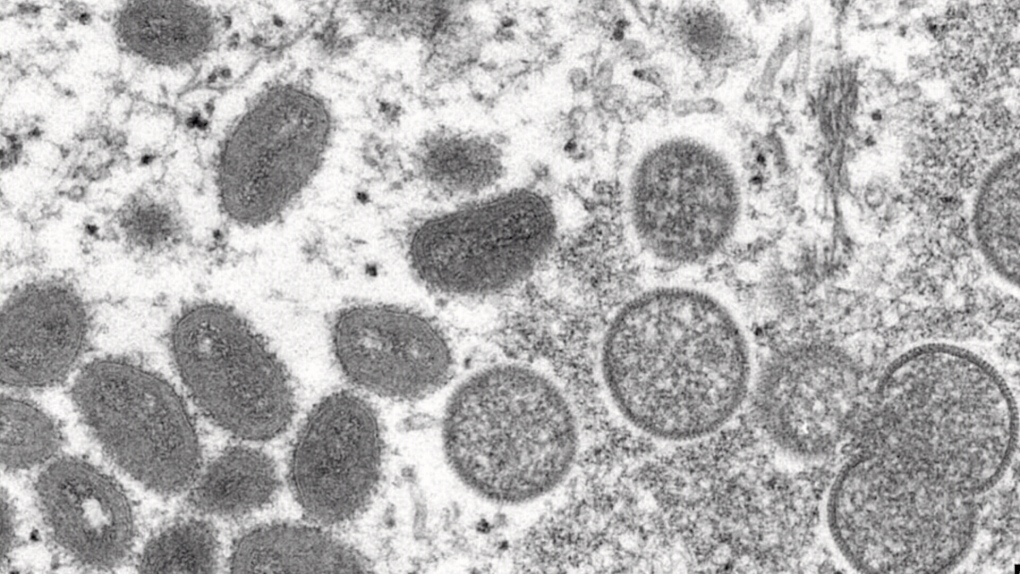

"Access to life-saving prevention tools, testing and treatment, whether for HIV, COVID-19 and now monkeypox, too, often relies on chance: where you were born, the colour of your skin and how much you earn," Tedros said.

The international AIDS conference runs until Tuesday at Montreal's downtown convention centre, Palais des congrès de Montréal. More than 9,000 delegates from around the world were scheduled to attend in person, with another 2,000 registered to participate remotely.

AIDS conference organizers have criticized the Canadian government for denying visas to hundreds of delegates and for International Development Minister Harjit Sajjan's decision to withdraw his participation on short notice.

Asked about the visa denials, Duclos described them as a "collective tragedy."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 1, 2022.

Federal government announces $18M for HIV testing at Montreal AIDS conference - CP24 Toronto's Breaking News

Read More