Department of Anesthesiology, Bengbu Medical College, Anqing Municipal Hospital, Anqing, People’s Republic of China

Introduction

Breast cancer is a common malignancy in women. Modified radical mastectomy (MRM) is an effective intervention for patients with breast cancer. Most patients who undergo MRM experience acute postoperative pain. Moreover, if acute postoperative pain is not sufficiently controlled, it may be develop chronic pain.1 Currently, and opioids are currently the mainstay of drugs for moderate or severe postoperative pain. However, opioid-related adverse events may also affect the quality of the postoperative recovery. Multimodal analgesia is usually used in postoperative pain management to control pain and reduce opioid requirements.

Dexmedetomidine (DEX), a selective α2 adrenal receptor agonist, has sedative and analgesic effects.2 Two meta-analysis revealed that DEX administration alleviated postoperative pain and reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV).3,4 Current evidence indicates that the use of DEX enhances postoperative recovery quality.5,6 Esketamine, the dextral isomer of ketamine, is an antagonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. It has higher potency, faster recovery time, and fewer adverse effects than ketamine.7,8 Some clinical studies have demonstrated that S (+)-ketamine administration can reduce the intensity of postoperative pain,9 decrease the requirement for postoperative analgesics,10 and prolong the analgesic time.11 Bornemann-Cimenti H et al found that S (+)-ketamine reduced opioid consumption and hyperalgesia after surgery.12 In addition, a clinical study showed that esketamine administration enhanced the quality of recovery by alleviating postoperative pain.13,14 However, the effect of esketamine combined with dexmedetomidine on the postoperative quality of recovery in patients undergoing MRM has not been reported. This study aimed to investigate whether the combination of esketamine and DEX administration further improves the quality of recovery after surgery in patients with MRM.

Methods and Materials

Study Participants

The present study was approved by The Ethics Committee of Anqing Municipal Hospital (2022028). The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (March 17, 2022; NO: NCT05283408) and implemented from April 2022 to March 2023. This study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from each patient who agreed to participate in the study one day before surgery. 135 female patients undergoing MRM with ASA I-II, aged 30–65 years were participated in our trial. The exclusion criteria included a history of preoperative psychiatric, renal, or hepatic insufficiency; severe respiratory or circulatory disease; preoperative atrioventricular block; pregnant or lactating women; and preoperative bradycardia.

Randomisation and Blinding

Participants were randomly divided into the dexmedetomidine group (group D), dexmedetomidine combined with low-dose esketamine group (group DE1), and dexmedetomidine combined with high-dose esketamine group (group DE2) at a 1:1:1 ratio using a computer-generated list of random numbers. The random numbers were sealed with opaque envelopes to conceal arm allocation. Patients were given 0.5 µg/kg dexmedetomidine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) and normal saline (20 mL) over 10 minutes before anesthesia induction, and 0.4 µg/kg/h dexmedetomidine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) and normal saline (20 mL) were continuously infused at 20 mL/h until 20 minutes before the end of surgery in group D, respectively. Patients were given 0.5 µg/kg dexmedetomidine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) and 0.5 mg/kg esketamine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) over 10 minutes before anesthesia induction, and 0.4 µg/kg/h dexmedetomidine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) and 2 µg/kg/min esketamine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) were continuously infused at 20 mL/h until 20 minutes before the end of surgery in group DE1, respectively. Patients were given 0.5 µg/kg dexmedetomidine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) and 0.5 mg/kg esketamine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) over 10 minutes before anesthesia induction, and 0.4 µg/kg/h dexmedetomidine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) and 4 µg/kg/min esketamine (a total of 20 mL with normal saline) were continuously infused at 20 mL/h until 20 minutes before the end of surgery in group DE2, respectively. Patients, anesthesia providers, surgeons, operating room nurses, and outcome assessors were blinded to the group allocation.

Anesthesia Protocol

Each participant entered the operating room, and routine monitoring including mean blood pressure (MBP), peripheral oxygen saturation (SPO2), electrocardiogram (ECG), and heart rate (HR) was established. The anesthesiologist recorded the baseline values during routine monitoring. An operating room nurse established an intravenous line to infuse the crystalloid solution. Dexamethasone 10 mg and penehyclidine 0.5 mg were given for each patient. All participants received preoxygenation with 100% oxygen for 3–5 minutes using a face mask. Midazolam 0.05 mg/kg, remifentanil 0.5 µg/kg (over 60 seconds), etomidate 0.3 mg/kg, and rocuronium 1.0 mg/kg were intravenously injected for induction of anesthesia. Tracheal intubation was performed when the patient lost consciousness and the jaw was relaxed. After tracheal intubation, a Fabius Draeger machine was attached to perform mechanical ventilation. The end-tidal CO2 pressure (PetCO2) was maintained between 35 and 45 mmHg by adjusting tidal volume (6–8 mL/kg) and respiratory rate (12–14 beat/min). The fraction of inspired oxygen was set at 50–60%. Flurbiprofen axetil 50 mg was intravenously administered before skin incision. Remifentanil 0.06–0.2 µg/kg/min and propofol 4–6 mg/kg/h were infused to maintain anesthesia during the perioperative period. cis-atracurium 1–2 mg was administered according to the surgical requirements. Hemodynamic variables were maintained within 20% of the baseline measurements. If the HR was < 50 beats/min during the intraoperative period, atropine 0.5 mg was administered intravenously. The infusion of dexmedetomidine and esketamine were stopped 20 minutes before the end of surgery, meanwhile, sufentanil 0.2 µg/kg and dezocine 0.1 mg/kg were injected for controlling postoperative pain. Propofol and remifentanil were discontinued at the end of skin suture. Ondansetron 4 mg was administered intravenously to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting. After endotracheal tube removal, patients were transferred to the PACU and continuously observed until they left the PACU.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was the total QoR-15 score according to the QoR-15 scale at 1 day after surgery. The total QoR-15 scores were evaluated based on physical comfort (five items), emotional state (four items), psychological support (two items), physical independence (two items), and pain (two items) for QoR-15 questionnaire. The total QoR-15 score ranges from 0 to 150 points, with higher scores representing better recovery quality after operation.15

Postoperative pain intensity was assessed using the VAS pain scale at 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours after surgery (0, painless; 10, worst imaginable pain). Patients were administered flurbiprofen axetil 50 mg when the postoperative VAS pain scores were ≥4. In addition, opioids are not routinely used for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy at our hospital. The awakening time was defined as the time when remifentanil and propofol were stopped to open the eye, and the extubation time was defined as the time when remifentanil and propofol were stopped to remove the endotracheal tube. An HR < 60 beats/min was considered indicative of bradycardia. The Ramsay Sedation Scale (RSS) was used to evaluate the level of sedation after surgery in the PACU (1 represents patient anxiety, agitation, or restlessness; 2 represents patient cooperation and orientation; 3 represents patient response to commands only; 4 represents asleep but strong response to stimulation; 5 represents asleep and slow response to stimulation; 6 represents asleep, no response). An RSS score of ≥4 was considered excessive sedation. The secondary outcomes included preoperative total QoR-15 scores; total QoR-15 scores at 3 days after surgery; perioperative remifentanil and propofol requirement; awaking time; extubation time; VAS pain scores at postoperative 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h; postoperative rescue analgesic; postoperative nausea and vomiting; bradycardia; excessive sedation; nightmares; and agitation within 30 min after surgery.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated using PASS 11.0 according to the primary endpoint of the present study. The results of our pilot study showed that the mean values and standard deviations (SD) of the total QoR-15 scores in all three groups were 125.3, 128.9, 130.0, 5.8, 3.8, and 4.2, respectively. Therefore, 37 patients in each group were required with an α of 0.05, and β=0.1. Allowing for a 20% dropout rate, we selected 135 patients for the present study.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS v.20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. Categorical data including ASA classification, rescue analgesic use, and the incidence of bradycardia, PONV, excessive sedation, nightmares, and agitation within 30 min after surgery were analyzed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, and are shown as number (proportion, %). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Levene’s test were used to evaluate the normality and homogeneity of continuous data, respectively. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean (SD) and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The total QoR-15 scores, VAS pain scores during the first 48 h after surgery, propofol dose, remifentanil dose, awaking time, extubation time, and PACU stay were reported as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

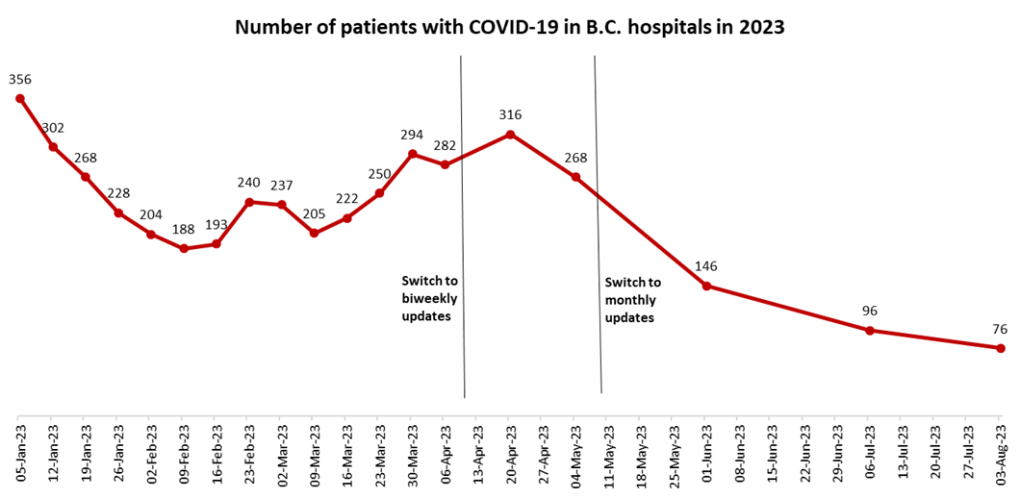

A total of 160 participants were recruited for the study. Eighteen participants did not meet the inclusion criteria, seven refused to participate in the study, and 135 completed the study (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 CONSORT flow diagram for the study.

|

The Comparison of the Baseline Data in Three Groups

There were no differences in age, operation time, anesthesia time, ASA grade, body mass index (BMI), fluid infusion volume, or blood loss (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Clinical Data of Patients

|

The Comparison of the Overall QoR-15 Scores Before and After Surgery

The preoperative overall QoR-15 scores did not differ among the three groups (P > 0.05). The overall QoR-15 scores were significantly higher in groups DE1 and DE2 than in group D 1 and 3 days after surgery (P = 0.000, P = 0.000, P = 0.003, P = 0.000, respectively). No significant difference was found in the overall QoR-15 scores between groups DE1 and DE2 at 1 and 3 days after surgery (P>0.05 and P > 0.05, respectively) (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Comparison of QoR-15 Scores at Different Time Points

|

The Comparison of VAS Pain Scores Within 48 h After Operation

The VAS pain scores at 6, 12, and 24 h postoperatively were significantly lower in the DE1 and DE2 groups than in the D group (all P < 0.05). The VAS pain scores at 2 and 48 h postoperatively were not significantly different among the three groups (all P > 0.05). The VAS pain scores during the first 48 postoperative hours did not differ significantly between the DE1 and DE2 groups (all P > 0.05) (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Comparison of VAS Pain Scores at Different Time Points

|

The Comparison of Intraoperative Remifentanil and Propofol Requirement, Awaking Time, Extubation Time, and PACU Stay

The intraoperative remifentanil and propofol requirements were significantly lower in groups DE1 and DE2 than in group D (all P = 0.000). There was no difference in intraoperative remifentanil requirement between the DE1 and DE2 groups (P > 0.05). Compared with group D, awakening time, extubation time, and PACU stay were significantly prolonged in the DE1 and DE2 groups (all P < 0.05). The awakening time, extubation time, and PACU stay were much longer in the group DE2 than in the group DE1 (all P = 0.000) (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Comparison of Propofol Dose, Remifentanil Dose, Awaking Time, Extubation Time, and PACU Stay

|

The Comparison of Postoperative Rescue Analgesic, Nausea and Vomiting, Bradycardia, Excessive Sedation, Nightmare, and Agitation Within 30 Min After Surgery

The proportion of postoperative rescue analgesics and bradycardia was higher in group D than in groups DE1 and DE2 (all P < 0.05). No significant difference was found with respect to bradycardia and postoperative rescue analgesic use between the DE1 and DE2 groups (P>0.05 and P > 0.05, respectively). Compared with group D, the incidence of excessive sedation was higher in groups DE1 and DE2 (P < 0.05, and P < 0.05, respectively). The incidence of PONV, nightmares, and agitation within 30 min after surgery was not significantly different among the three groups (all P > 0.05) (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Comparison of Postoperative Rescue Analgesic, Nausea and Vomiting, Bradycardia, Excessive Sedation, Nightmares, and Agitation Within 30 Min After Surgery

|

Discussion

The results of our study indicate that dexmedetomidine combined with esketamine partly improves postoperative recovery quality, alleviates postoperative pain intensity, and decreases the incidence of bradycardia and rescue analgesia compared with dexmedetomidine alone in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer. However, the combination of dexmedetomidine and esketamine prolonged awakening time, extubation time, and PACU stay, especially dexmedetomidine combined with high-dose esketamine (4 µg/kg/min).

The quality of postoperative recovery was evaluated based on the total QoR-15 score, which is an effective tool in clinical practice. It was reported that ketamine with sub-anesthetic dose improved the quality of recovery after surgery in colorectal cancer patients by antidepressant and analgesic effect.16 Yu et al revealed that pectoral nerve block type II combined with esketamine enhanced postoperative recovery quality for breast cancer.17 Zhu et al demonstrated that low- or high-dose esketamine improved the quality of postoperative recovery on postoperative days 1 and 3.18 Some clinical studies proved that dexmedetomidine administration alleviated the intensity of postoperative pain, experienced lower postoperative nausea and vomiting, and improved postoperative quality of recovery.19–21 In the present study, we found that there were higher QoR-15 scores in groups DE1 and DE2 than in group D on postoperative days 1 and 3, suggesting that dexmedetomidine combined with esketamine infusion provided better quality of postoperative recovery, which may be related to lower VAS pain scores and improved QoR-15 questionnaire.

Perioperative management of analgesia minimizes the use of opioids, based on the concept of enhanced recovery after surgery. Some evidence showed that dexmedetomidine had an opioid-sparing effect and alleviated postoperative pain intensity.22,23 Zhang et al found that intravenous dexmedetomidine reduced postoperative VAS pain scores within the first 24 h of undergoing modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer.24 In addition, López et al revealed that ketamine had a lower ratio of acute postoperative pain, alleviated intensity of pain, and reduced rescue analgesia requirement in breast cancer.25 Meta analysis by Bi et al showed that ketamine effectively reduced wound pain, decreased incidence of postmastectomy pain syndrome, and improved depression after surgery.26 Dexmedetomidine combined with esketamine infusion improved postoperative analgesia.27 The results of our study found that dexmedetomidine combined with esketamine was significantly decreased postoperative VAS pain scores at 6, 12, 24 h, and the rate of postoperative rescue analgesic compared to dexmedetomidine administration. This indicates that the combination of dexmedetomidine and esketamine controlled postoperative pain better than dexmedetomidine alone, which may be related to esketamine analgesia28 or the additive analgesic effect of dexmedetomidine combined with esketamine administration.29

Dexmedetomidine and esketamine have opioid-sparing effects. Some studies have suggested that intravenous dexmedetomidine reduces intraoperative opioid requirement.22,30 Zhu et al argued that intravenous ketamine had an opioid-reducing effect.31 Our results showed that dexmedetomidine combined with esketamine further reduced intraoperative remifentanil requirement compared with dexmedetomidine alone, which implies that dexmedetomidine combined with esketamine had a better opioid-sparing effect. In addition, our results also showed that the propofol requirement was lower in groups DE1 and DE2 than in group D.

Intravenous dexmedetomidine had a longer time to awaken and extubation.32,33 Esketamine infusion may prolong recovery time.34 Chen et al reported that dexmedetomidine combined with esketamine administration lengthened awakening time in patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery.35 In the present study, we found that awake time, extubation time, and PACU stay were longer in groups DE1 and DE2 than in group D, in addition, they were longer in group DE2 than in group DE1. The results showed that dexmedetomidine plus esketamine resulted in better sedation in a dose-dependent manner.

The use of dexmedetomidine results in a higher rate of bradycardia during the perioperative period. It was reported that dexmedetomidine infusion significantly increased the incidence of bradycardia.36 Single low-dose esketamine administration experienced transient tachycardia.37 We observed that the combination of dexmedetomidine and esketamine had lower rate of bradycardia than dexmedetomidine during the perioperative period, which may be associated with tachycardia-induced esketamine and continuous infusion of esketamine.

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, we observed only a few adverse effects of esketamine, such as nightmares. However, esketamine may cause hallucinations, visual disturbances, confusion, and disorientation. However, further studies are required to confirm these adverse effects. Second, we only evaluated pain scores during the first 48 hours after surgery, which does not reflect long-term outcomes; postoperative chronic pain affects patient satisfaction and quality of life. Therefore, we need to further evaluate the effect of dexmedetomidine plus esketamine infusion on postoperative chronic pain. Third, dexmedetomidine and esketamine may affect hemodynamic changes. Therefore, the effect of their combination on hemodynamic changes should be further evaluated. Finally, the sample size was small and this was a single-center trial, and the results of this study require a multi-center and large sample for further confirmation.

Conclusion

Dexmedetomidine combined with esketamine partly improved postoperative recovery quality, alleviated postoperative pain intensity, and decreased the incidence of bradycardia and rescue analgesia compared with dexmedetomidine alone in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy. However, the combination of dexmedetomidine and esketamine prolonged awakening time, extubation time, and PACU stay, especially dexmedetomidine combined with high-dose esketamine (4 µg/kg/min). The lower dose of esketamine infusion was better than the higher dose in combination with dexmedetomidine infusion.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This study was supported by the Clinical Research Foundation of Hubei and Chen Xiaoping Science and Technology Development Foundation (CXPJJH12000005-07-43).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Wang X, Ran G, Chen X, et al. The effect of ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block combined with dexmedetomidine on postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Ther. 2021;10(1):475–484. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00234-9

2. Tasbihgou SR, Barends CRM, Absalom AR. The role of dexmedetomidine in neurosurgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2021;35(2):221–229. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2020.10.002

3. Sin JCK, Tabah A, Campher MJJ, Laupland KB, Eley VA. The effect of dexmedetomidine on postanesthesia care unit discharge and recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2022;134(6):1229–1244. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000005843

4. Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Hu T, et al. Dexmedetomidine reduces postoperative pain and speeds recovery after bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022;18(6):846–853. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2022.03.002

5. Miao M, Xu Y, Li B, Chang E, Zhang L, Zhang J. Intravenous administration of dexmedetomidine and quality of recovery after elective surgery in adult patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Anesth. 2020;65:109849. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.109849

6. Xu S, Liu N, Yu X, Wang S. Effect of co-administration of intravenous lidocaine and dexmedetomidine on the recovery from laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Minerva Anestesiol. 2023;89(1–2):10–21. doi:10.23736/S0375-9393.22.16522-3

7. Wang J, Huang J, Yang S, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of esketamine in Chinese patients undergoing painless gastroscopy in comparison with ketamine: a randomized, open-label clinical study. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:4135–4144. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S224553

8. Jelen LA, Young AH, Stone JM. Ketamine: a tale of two enantiomers. J Psychopharmacol. 2021;35(2):109–123. doi:10.1177/0269881120959644

9. Zhang T, Yue Z, Yu L, et al. S-ketamine promotes postoperative recovery of gastrointestinal function and reduces postoperative pain in gynecological abdominal surgery patients: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Surg. 2023;23(1):74. doi:10.1186/s12893-023-01973-0

10. Nielsen RV, Fomsgaard JS, Nikolajsen L, Dahl JB, Mathiesen O. Intraoperative S-ketamine for the reduction of opioid consumption and pain one year after spine surgery: a randomized clinical trial of opioid-dependent patients. Eur J Pain. 2019;23(3):455–460. doi:10.1002/ejp.1317

11. Wang H, Duan C, Zhang J, et al. Evaluation of the effect of perioperative administration of S(+)-ketamine hydrochloride injection for postoperative acute pain in children: study protocol for a prospective, multicenter, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, pragmatic clinical trial. Trials. 2022;23(1):586. doi:10.1186/s13063-022-06534-z

12. Bornemann-Cimenti H, Wejbora M, Michaeli K, Edler A, Sandner-Kiesling A. The effects of minimal-dose versus low-dose S-ketamine on opioid consumption, hyperalgesia, and postoperative delirium: a triple-blinded, randomized, active- and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016;82(10):1069–1076.

13. Yuan J, Chen S, Xie Y, et al. Intraoperative Intravenous infusion of esmketamine has opioid-sparing effect and improves the quality of recovery in patients undergoing thoracic surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain Phys. 2022;25(9):E1389–E1397.

14. Cheng X, Wang H, Diao M, Jiao H. Effect of S-ketamine on postoperative quality of recovery in patients undergoing video-assisted thoracic surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022;36(8):3049–3056. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2022.04.028

15. Li H, Huang D, Qiao K, Wang Z, Xu S. Feasibility of non-intubated anesthesia and regional block for thoracoscopic surgery under spontaneous respiration: a prospective cohort study. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2019;53(1):e8645. doi:10.1590/1414-431x20198645

16. Ren Q, Hua L, Zhou X, et al. Effects of a single sub-anesthetic dose of ketamine on postoperative emotional responses and inflammatory factors in colorectal cancer patients. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:818822. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.818822

17. Yu L, Zhou Q, Li W, et al. Effects of esketamine combined with ultrasound-guided pectoral nerve block type ii on the quality of early postoperative recovery in patients undergoing a modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Res. 2022;15:3157–3169. doi:10.2147/JPR.S380354

18. Zhu M, Xu S, Ju X, Wang S, Yu X. Effects of the different doses of esketamine on postoperative quality of recovery in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2022;16:4291–4299. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S392784

19. Shu T, Xu S, Ju X, Hu S, Wang S, Ma L. Effects of systemic lidocaine versus dexmedetomidine on the recovery quality and analgesia after thyroid cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Ther. 2022;11(4):1403–1414. doi:10.1007/s40122-022-00442-5

20. Ren B, Cheng M, Liu C, et al. Perioperative lidocaine and dexmedetomidine intravenous infusion reduce the serum levels of NETs and biomarkers of tumor metastasis in lung cancer patients: a prospective, single-center, double-blinded, randomized clinical trial. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1101449. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1101449

21. Sivaji P, Agrawal S, Kumar A, Bahadur A. Evaluation of lignocaine, dexmedetomidine, lignocaine-dexmedetomidine infusion on pain and quality of recovery for robotic abdominal hysterectomy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2022;72(5):593–598. doi:10.1016/j.bjane.2021.10.005

22. Shankar K, Rangalakshmi S, Kailash P, Priyanka D. Comparison of hemodynamics and opioid sparing effect of dexmedetomidine nebulization and intravenous dexmedetomidine in laparoscopic surgeries under general anesthesia. Asian J Anesthesiol. 2022;60(1):33–40. doi:10.6859/aja.202203_60(1).0005

23. Wang YL, Kong XQ, Ji FH. Effect of dexmedetomidine on intraoperative Surgical Pleth Index in patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic lung lobectomy. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;15(1):296. doi:10.1186/s13019-020-01346-1

24. Zhang Y, Jiang W, Luo X. Remifentanil combined with dexmedetomidine on the analgesic effect of breast cancer patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy and the influence of perioperative T lymphocyte subsets. Front Surg. 2022;9:1016690. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2022.1016690

25. López M, Padilla ML, García B, Orozco J, Rodilla AM. Prevention of acute postoperative pain in breast cancer: a comparison between opioids versus ketamine in the intraoperatory analgesia. Pain Res Manag. 2021;2021:3290289. doi:10.1155/2021/3290289

26. Bi Y, Ye Y, Zhu Y, Ma J, Zhang X, Liu B. The effect of ketamine on acute and chronic wound pain in patients undergoing breast surgery: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Pain Pract. 2021;21(3):316–332. doi:10.1111/papr.12961

27. Modir H, Moshiri E, Yazdi B, Kamalpour T, Goodarzi D, Mohammadbeigi A. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine-ketamine vs. Fentanyl-ketamine on saturated oxygen, hemodynamic responses and sedation in cystoscopy: a double blinded randomized controlled clinical trial. Med Gas Res. 2020;10(3):91–95. doi:10.4103/2045-9912.296037

28. Wang P, Song M, Wang X, Zhang Y, Wu Y. Effect of esketamine on opioid consumption and postoperative pain in thyroidectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;89(8):2542–2551. doi:10.1111/bcp.15726

29. Lee KH, Lee SJ, Park JH, et al. Analgesia for spinal anesthesia positioning in elderly patients with proximal femoral fractures: dexmedetomidine-ketamine versus dexmedetomidine-fentanyl. Medicine. 2020;99(20):e20001. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000020001

30. Coeckelenbergh S, Doria S, Patricio D, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine on Nociception Level Index-guided remifentanil antinociception: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021;38(5):524–533. doi:10.1097/EJA.0000000000001402

31. Zhu T, Zhao X, Sun M, et al. Opioid-reduced anesthesia based on esketamine in gynecological day surgery: a randomized double-blind controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022;22(1):354. doi:10.1186/s12871-022-01889-x

32. Gao S, Wang T, Cao L, Li L, Yang S. Clinical effects of remimazolam alone or in combination with dexmedetomidine in patients receiving bronchoscopy and influences on postoperative cognitive function: a randomized-controlled trial. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45(1):137–145. doi:10.1007/s11096-022-01487-4

33. Beloeil H, Garot M, Lebuffe G, et al.; POFA Study Group, SFAR Research Network. balanced opioid-free anesthesia with dexmedetomidine versus balanced anesthesia with remifentanil for major or intermediate noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2021;134(4):541–551. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000003725

34. Zhang C, He J, Shi Q, Bao F, Xu J. Subanaesthetic dose of esketamine during induction delays anaesthesia recovery a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022;22(1):138. doi:10.1186/s12871-022-01662-0

35. Chen L, He W, Liu X, Lv F, Li Y. Application of opioid-free general anesthesia for gynecological laparoscopic surgery under ERAS protocol: a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023;23(1):34. doi:10.1186/s12871-023-01994-5

36. De Cassai A, Boscolo A, Geraldini F, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine on hemodynamic responses to tracheal intubation: a meta-analysis with meta-regression and trial sequential analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2021;72:110287. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110287

37. Li J, Wang Z, Wang A, Wang Z. Clinical effects of low-dose esketamine for anaesthesia induction in the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022;47(6):759–766. doi:10.1111/jcpt.13604